Last year, Ivan Wise interviewed me for his Better Known podcast, where each guest names six things they think should be better known. Here’s a transcript of the episode.

Ivan Wise: Hello, you’re listening to Better Known, where each episode a guest makes a series of recommendation of things which they think should be better known. Our recommendations include interesting people, places, objects, stories, experiences and ideas, which our guests feel haven’t had the exposure that they deserve. The only conditions for discussion are that our guests loves it and think it merits your attention as well. This weeks guest on Better Known is David Singleton.

David Singleton: It’s a pleasure.

Ivan Wise: While you were making your list of six choices, were there any that were bubbling under that just missed out that you felt favourably about but didn’t quite include?

David Singleton: Yes, I suppose there are some things that I wish I could’ve included but I think that they’re probably already quite well known. But in general I think anything related to the amazing complexity and interdependence of the world that we live in, in terms of people and social networks as well as the scale and the beauty of the universe and the cosmos.

Ivan Wise: So, the first choice that you’ve made is something called Tardigrades. Now, I have to be honest, I’d never heard of this. I had no idea what it was. I looked it up and discovered it was a micro animal. So, why do you think they’re more interesting than any other micro animal?

David Singleton: Tardigrades are also often called water bears, so you might have heard of that. Apparently, and I only found this out when I was doing research to talk to you today, they’re also sometimes called moss piglets. So, they are animals. They are nearly microscopic. In many cases they are microscopic and they have these long bodies with little legs and scrunched up heads that look a bit like a Dalek or something. In fact I discovered a website that said that they look like the Hookah smoking caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland. And if you’ve seen Alice in Wonderland the movie, they do look just like that.

David Singleton: And I think they’re really interesting because first of all, they’re not just a single animal, it’s actually a phylum of animals, so that’s quite a large group. There are over 1000 species. And they mostly, they live in water, mostly at the bottom of lakes and stuff. And they feed on algae, lichens and moss. But some species are actually carnivores and eat other Tardigrades, which is pretty cool, but what’s really great about them and I think what makes them unique is that they are amazing at surviving really harsh conditions.

Ivan Wise: So, they would be the sort of creature that would survive nuclear war.

David Singleton: Yes, I think so. So, in fact scientists at Harvard and Oxford did an analysis of which species on earth might survive really extreme conditions and they concluded that Tardigrades would actually survive if there was a nearby stellar event. A supernova, which is probably one of the most extreme things that could happen to the earth. So, it kind of gives me a lot of optimism for the resilience of live, ‘cause I guess they can go on and evolve into something significantly more interesting, but the way that they survive is really cool. They dry themselves out and turn into little balls called Tuns and then that allows them to survive really long periods of extreme heat and cold.

David Singleton: They’ve even survived in low earth orbit on the outside of the international space station, which is pretty cool. And the reason that I got really interested in them recently was I read a book called The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu. He has this alien species, I won’t spoil it too much, that are discovered and they have this interesting property that their bodies dry out for thousands of years at a time to survive real extremes of heat and cold. And at the time it seemed completely fantastical and then I was reading around and discovered that there actually is a species of animal on earth that does this, which I thought was pretty amazing.

Ivan Wise: And why do you think they’re not better known? Because obviously everybody always talks about cockroaches surviving nuclear war, but they don’t mention these.

David Singleton: I have no idea. I didn’t come across them in any of my education at school and it wasn’t until I saw a documentary I first came across them. So, I think they’re just underappreciated and we should all learn to love the Tardigrade.

Ivan Wise: And is it possible to get one as a pet?

David Singleton: I imagine we probably all have a whole bunch of them living in our houses already. So, it’s actually a pretty cool idea that you could ship them to people ‘cause they would obviously survive a long journey with a little microscope and you can maybe plug it into your TV and watch the Tardigrades floating around. Seems like a good business idea.

Ivan Wise: Okay. So, it sounds like Tardigrades should be better known. Your next choice is the subject of fractals. Now, I have known a little bit about fractals. We featured them on our second episode, but this hasn’t unfortunately yet helped them become better known. So, what are fractals and why do you think more people should know about them?

David Singleton: So, a fractal is a shape which is made of parts that are similar to the whole. And in fact, as you zoom in and zoom in and zoom in and zoom in, you’d find infinitely more detail as you go and at each level it looks quite similar to the thing from the furthest zoomed out level. And I think many people typically encounter fractals for the first time when they’re learning about computer graphics. If you’re learning to program computer graphics, a very short piece of computer code can describe a wonderfully complex and actually really beautiful pattern. So, it’s a really simple way to do something that’s just amazingly mind blowing to look at.

David Singleton: In actual fact, nature is also fractal if you think about its invariance of scale, because if you think about a mountain, if you see a mountain from far away and squint at it and ignore all the little people wandering around on it or whatever, it can look very similar to a small piece of rock or a little outcrop that’s viewed up close. So, in many ways nature is fractal.

Ivan Wise: And so, when were fractals first noticed or discovered by us? When did they get named?

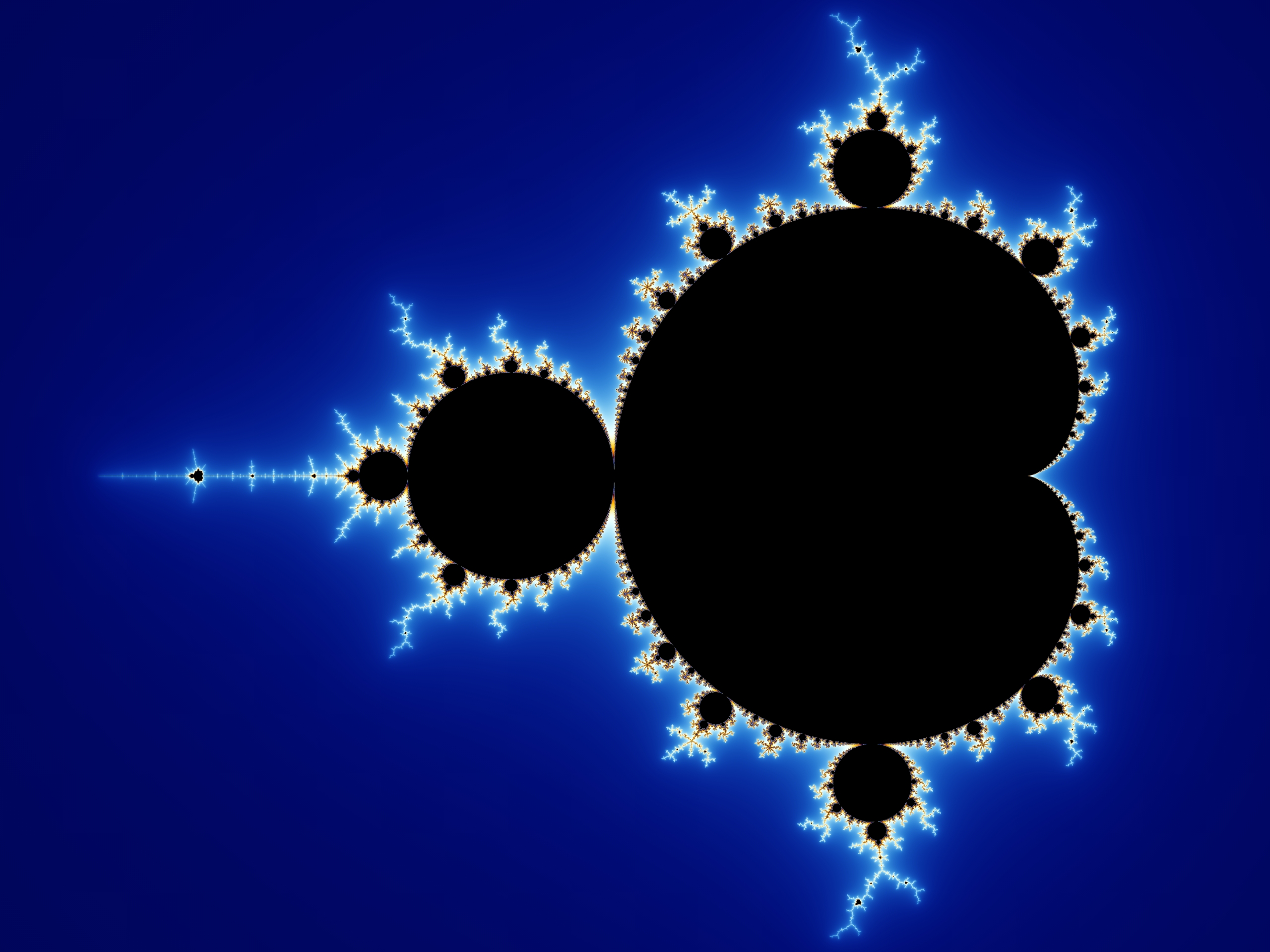

David Singleton: I believe that they were first discovered in the late 19th century. This concept that you could have a pattern that you could continually zoom in to. And indeed on your second episode, there’s a great little interlude about the fractalists during the first world war period. So, those folks first understood the mathematics. But they really became much better understood in the 80s when computers became powerful enough to actually allow us to draw them and look at them and zoom in and out. And one of the most famous is the Mandelbrot set. At its most zoomed out level, it looks like it has three big circles and then as you look more closely at the perimeter of each of those circles, blooming from each one are more and more circles.

David Singleton: And as you get closer and closer or further and further “in” to the Mandelbrot set you see that these interconnected circles meander in ways that look like valleys and rivers and indeed as you zoom into each one of those little rivers, you’ll find gatherings of the water that look just like the big picture rotated a little bit. And as you zoom in hundreds, thousands, millions, billions, zillions of times, it will have that selfsame structure that it had right at the top level. And it’s amazingly intricate and it’s amazing because this is a thing that just exists. It’s just there in the mathematics. So, the actual space in which this particular Mandelbrot set is understood is just numbers - the numbers along with the horizontal direction are the regular numbers that we all know and the vertical axis are what are called imaginary numbers. They’re not really imaginary, but they’re related to the square root of minus one, which is why we call them imaginary.

David Singleton: And the actual mathematics of deciding whether any particular spot on that surface is part of the Mandelbrot set or is right on the edge, which has this really intricate structure, is actually a really, really, simple piece of mathematics. But when you apply it again and again and again and look at how it behaves across this whole surface, you end up with this really, really intricate, even infinitely intricate structure that is just genuinely beautiful.

Ivan Wise: And how is this of use to us having discovered this and learn more about it in the 80s? How are we now using this knowledge?

David Singleton: I don’t know that they are particularly useful. There are definitely uses where some of these fractal patterns are used to compress data. Because they have this intricate structure, if you can find something that, within that intricate pattern that relates to something that you’re trying to describe, it’s a really efficient way of describing it. Like I mentioned, you can write a really short computer program that draws a picture that is extremely beautiful. But I think there’s almost something more profound here, which is this is a beautiful thing that just exists in the universe. It’s just there in the mathematics. You can’t touch it, but it’s always there and no matter whether you’re on earth or you’re at the edge of the universe, this thing still exists and it’s still this beautiful pattern.

Ivan Wise: So, as an aesthetic thing that you appreciate it.

David Singleton: Precisely.

Ivan Wise: Sounds like fractals should be better known for the second time. Your next choice is a Nobel Prize winner called William Shockley. Again a name completely unknown to me. So, who was William Shockley?

David Singleton: So, William Shockley was born in London to American parents and he was raised in his family’s home town of Palo Alto, California. And many of you may recognize that Palo Alto California is right in the heart of Silicon Valley. And it was actually William Shockley who established Silicon Valley as a thing.

Ivan Wise: So, he built it did he?

David Singleton: Well, certainly without William Shockley Silicon Valley would not be in Silicon Valley and that is one of the reasons he’s interesting. He’s probably not well known, because in his later life he developed some pretty controversial opinions and certainly had some ideas about race that I personally find abhorrent. And I think that many of the reasons why he’s not better known is that he distanced himself from the mainstream of thought and certainly by the end of his life was not someone that a lot of people wanted to associate with. So, he helps remind us all that there’s a high price to a bad reputation.

Ivan Wise: So, his initial career was as a physicist, is that right?

David Singleton: Correct. Together with John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at Bell labs he essentially invented the transistor, which underlies all of digital computing. There’d been some work in the transistor effect before, but he, William Shockley wrote a book called Electrons and Holes in Semiconductors. And that is the theory that actually underlies the transistor effect and digital computing on Silicon wafers, which is what underlies all of computing today. What’s pretty interesting is, he did that at Bell Labs on the east coast of the US and then he together with the others I mentioned, they won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1956. And shortly thereafter he decided to try to commercialize what they’d done and he started a group called Shockley Semiconductor.

David Singleton: And he did that back in Palo Alto California because I guess he moved back to support his elderly mother. So, it is literally William Shockley’s family connections that caused Silicon valley to be founded where it was. But although he was a brilliant physicist by all accounts, he was apparently a horrible manager and his way could be generally summed up as being domineering and increasingly paranoid. So, he was good at hiring people, but he wasn’t good at retaining people. And famously the Traitorous eight were eight Shockley Semiconductor employees who left and formed another company called Fairchild Semiconductor and went on to create the mass market for transistors in digital computing and indeed two of the Fairchild folks left to start Intel, which of course we all know and many of us love today.

Ivan Wise: Has the Shockley management style been retained in Silicon Valley or have they learned against that?

David Singleton: Well, I hope that it serves as a reminder that being brilliant technically and not being able to keep a team together isn’t the best way to success, although I think obviously we would probably see lots of examples of possibly the Shockley management style out there. But hopefully everyone can aspire to doing better in learning from his example.

Ivan Wise: And what was his role in the planning for the bombing of Japan in the second world war? How was he involved in that?

David Singleton: When world war two broke out, Shockley was at Bell Labs working with his research group, but of course everyone got drafted into the war effort. So, initially he was working on radar and then on anti-submarine tactics. But at some point he was commissioned to do a study on the probable casualties from an invasion of the Japanese mainland. So, I guess this was in 1944 and it was getting towards the end of the war and there was an expectation that the US would have to send troops to Japan. So, he concluded that if the way the conflicts between Japanese and American and allied troops had gone on throughout the Pacific was repeated that a ground invasion of the Japanese mainland would actually result in very, very high casualties. So, he, in fact, his report, estimated that between five and ten million Japanese and between 1.7 and 4 million allied troops would be killed or at least would be casualties. Not all of those may have been killed.

David Singleton: And in fact I think that study was in many ways used as justification for dropping the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki with that kind of greater mercy rationale - the idea that this would bring a swifter end to the war and would actually result in fewer casualties or deaths.

Ivan Wise: Yeah, absolutely and extraordinarily someone of his influence is something that didn’t then happen as a result of his research. And you say his legacy today is partly tainted by some of his views. Is he still remembered? Is he well known within the physics community?

David Singleton: He’s certainly not an obscure individual, but he’s definitely not well known. There’s just one biography of William Shockley and as far as I can tell, it’s currently out of print.

Ivan Wise: Okay. So, William Shockley should be better known. You’re listening to Better Known with my guest today, David Singleton, who’s been choosing a series of things which he thinks should be better known. So far we’ve had Tardigrades, we’ve had fractals and we’ve had William Shockley. But we’ve been very positive so far in all our conversation, but as well as thing that should be better known, is there anything for you really famous that you wish was much less well known?

David Singleton: Those little cups of prepacked coffee beans that you put into a machine and pull a lever and a cup of coffee pops out. First of all I think the whole ritual of making coffee, whether it’s from instant or from beans is part of the fun of making a cup of coffee, but also they cause a tremendous amount of waste. And I don’t actually think they add anything to the overall quality of the cup of coffee that you get or the overall experience. So, I wish those little coffee cup things were much less well known.

Ivan Wise: So, your next choice is a lough. Now most people associate loughs with Scotland, but you’d like to discuss one that’s in Northern Ireland. So, what is that?

David Singleton: Indeed, very dear to my heart, Strangford Lough, it is one of two famous, but maybe not famous enough loughs in Northern Ireland. So, mostly I think we think of a lough as being a lake and indeed the biggest lough in Northern Ireland, which is called Lough Neagh is a lake right in the center. So, if you ever see a map and there’s that big bit of water in Northern Ireland, that’s Lough Neagh. But loughs can also actually be open to the sea. Both in Northern Ireland and in Scotland. And the one I’d like to talk about today is Strangford Lough. So, if you look all the way across to the east side of a map of Northern Ireland you’ll see a little hook and there’s a very narrow inlet to the sea and then a large sea connected lake I guess, which is called Strangford Lough.

David Singleton: So, it’s enclosed by the Ards Peninsula on the east and then the rest of County Down to the west. And it is a really large sea inlet. It’s actually the largest inlet in the British Isles. So, apparently it covers a 150 square kilometers. Because it is completely enclosed, it has really amazing wildlife, both sea life and sea birds. But what I like about it the most and I grew up nearby and indeed my mother’s side of the family were mostly from this part of the world, the landscape of that part of County Down is covered in drumlins. So, drumlins are these little hillocks I guess that were formed as ice retreated at the end of the ice age. And so, across County Down you’ll see lots of little drumlins. It means that you have all these marshy bog areas between them, but as they roll out into the sea at Strangford Lough, you end up with a pattern of lots and lots and lots of islands because the little dips between the drumlins are filled with water and then the tops of the drumlins stick out.

David Singleton: And if you see this from a hill above Strangford Lough, it’s just a beautiful landscape which rolls out in front of you and honestly two of these choices I made today are connected. It reminds me very deeply of the fractals in the Mandelbrot set and it just shows how nature and mathematics are in some really weird way connected. But it’s also a really great part of the world to visit and in fact one of the things that’s most amazing is at the very tip there’s a very narrow channel as it goes out to sea and there’s actually a little passenger ferry that goes between Strangford and Portaferry on the other side that will take you across that little inlets saving you a very, very, very long drive all the way around the Ard side. And it’s just a piece of the world that I love to spend time in. And I’ve never heard of anyone outside of Northern Ireland traveling to get to. And I think it’s a wonderful part of the world and you should go check it out.

Ivan Wise: Absolutely. And you first went there presumably as a child?

David Singleton: Indeed. In fact, I spent many happy weekend days all around Strangford Lough visiting nature reserves, little restaurants and of course family and friends.

Ivan Wise: So, Strangford Lough I think should be better known. Your next choice is a website, which again I’ve never heard of, with regular links to quite a variety of articles. So, what’s it called?

David Singleton: It’s called kottke.org. K-O-T-T-K-E dot org by a guy called Jason Kottke, which I personally have been visiting pretty much every day since I discovered it. Jason Kottke was friends with a lot of the really early people in the web 2.0 movement. A lot of early bloggers. And has been keeping this pretty sublime set of links to other interesting stuff on the web up to date almost every day since March 1998. So, the kind of topics that you can expect to see there are posts on things like arts, technology, science, visual culture, design, music, et cetera, et cetera. And I just find it to be a fantastic collection of stuff that I personally find universally or almost universally interesting and unexpected and otherwise wouldn’t encounter.

David Singleton: And he actually has quite a knack for discovering things that are happening on the web before they become mainstream and I like to go visit this site so that I can be a little bit ahead of the curve. In fact, I’m kind of obsessed with it. It’s definitely one of my daily browsing habits.

Ivan Wise: And so, it’s just a one man band. So, how does he do enough reading to get all these interesting articles?

David Singleton: So, he does do this as his full-time job. In fact, when he started I think he had other jobs doing web design and so forth. But at some point within the last 20 years, which I can’t quite remember, he actually decided to see if he could fund doing this as a full-time job through patronage, through all the people who wanted to actually giving him donations to run the site. And he managed to do that for a full year. I think he called it Ramen profitable. Meaning that he was able to just about pay his bills and pay for pretty cheap food, but nothing more.

David Singleton: And nowadays it has very subtle advertising and yeah, I guess he must spend almost his whole day looking around the web. Of course, because it is at least somewhat well known in some circles, I think a lot of people will send him great content.

Ivan Wise: And just give us a particular example of an article you read recently that you thought was interesting or a particular theme that you came across.

David Singleton: Yeah, well, in fact, today there’s one which I really enjoyed, which was about finding your museum doppelganger. Some people apparently have been lucky enough to find themselves in paintings in art museums. So, they’re literally walking around in art museum and look at the person in the portrait and think, “Oh my goodness, that looks just like me”. And there’s some fantastic pictures on here today. Again, he doesn’t write this stuff from scratch, he finds it elsewhere on the web. So, some of you might already have heard of this. But he was also mentioning that there is a new app from Google arts and culture that lets you take a selfie and find your own art doppelganger.

David Singleton: So, that’s an example just from today. Probably the most famous post was that he somehow discovered that the longest running contestant on Jeopardy was about to end his winning streak. He was called Ken Jennings. And the news of that was broken on the site kottke.org. I also particularly remember a series of posts about Flash games. So, I don’t know if you remember, this is around 10 years ago that on the web there were lots of these little toy games that you could play for 15, 20 minutes and they’d be lots of fun. And he did a great job of going out and figuring out which ones were the most fun and the most worthy of wasting our time on and those were particularly useful.

Ivan Wise: Okay, so kottke.org should be better known. Your final choice is straight 8, which I believe is a film making competition, is that right?

David Singleton: It is.

Ivan Wise: And so, what is it exactly?

David Singleton: So, straight 8 is a film making competition. It is quite unique in that you make a film on a single cartridge of super 8 film. So, for those of you who are not already familiar with super 8, it’s the kind of film that you would have had in a home cine camera in the 50s, 60s, 70s into the 80s. Before digital camcorders were a thing. And the way super 8 worked, was you got a cartridge of film, you put it into a relatively affordable camera. You pull the trigger on the camera, point it at whatever you wanted to record and then when the cartridge was depleted full of great memories, you took it to the chemist and posted it off when it came back and you could play it back on that little cine projector in your own home.

David Singleton: So, it was the way that most people made home movies for years and years and years. And this is now a competition to really look at the constraints of super 8 as a kind of art. So, as a film maker you compete with lots of other people from around the world. These days you buy your own cartridge of super 8, although it used to be that you were sent one. And you then go out and shoot a film. You have to return the super 8 cartridge when you finished shooting. And the people who run it actually develop the film. And the first time that you as a film maker will ever see it is if you are sitting in a premiere and they play it back.

David Singleton: So, it’s pretty nail biting stuff. But the thing that’s most unique is of course the art of film making today involves a lot of editing and with super 8 and the straight 8 competition in particular, you shoot the entire film, has to be in linear order, because you can’t go back and move things around, in camera. So, there is no editing. You edit by starting and stopping the camera.

Ivan Wise: That’s extraordinary.

David Singleton: And as a constraint that means there is tremendous art to creating something that is actually watchable. But some of the film makers do an astonishingly amazing job. Indeed, one of the most amazing ones I saw they had a car driving along, someone trying to flag it down and then the car drove over a cliff and crashed at the bottom. And then the same thing happened again, and again and again and again and if you realize, this thing could never have been edited, there’s no way to duplicate it. It was all shot in camera. That means they actually had to crash four cars to get that piece of footage. And they had to somehow act it out in exactly the same way every time. And of course there are devices like that, but there are also some amazing stories told through the competition.

Ivan Wise: And how long are the films that they make?

David Singleton: The films all last 3 minutes and 20 seconds or no more than 3 minutes and 20 seconds, because that is the full length of a canister of super 8.

Ivan Wise: And have you been to one of the screenings?

David Singleton: Not only have I been to one of the screenings, I have also entered the competition twice. And they are absolutely riveting and extremely exciting events. Just because no one in the theater except for the people who made the decision of which ones would get shown has actually seen the movies before.

Ivan Wise: And how many people enter each year? How big of a thing is it?

David Singleton: It has varied in size. So, I think they do a couple of competitions a year. The main one I think they have a 100 entries and then they do what’s called a straight 8 industry shootout where I guess they get people who are insiders in the film making industry to do it over the course of just a few days towards the end of the year. It is good timing if you’re inspired to take part in straight 8. You can go to their website today and you can actually still enter for 2018. They are not paying me to say this by the way. I just think it’s a really fantastic event.

Ivan Wise: Excellent. Okay, well, straight 8 should also be better known. So, that’s the end of your list. So, today we’ve had a micro animal, fractals for a second time, a Nobel Prize winning physicist, a lough in Northern Ireland, a website and a film making competition. So, out of the six choices, which one do you feel most strongly should be better known?

David Singleton: I have to just go back to my roots and say I think Strangford Lough is the place in the world that should be better known.

Ivan Wise: Okay, Strangford Lough it is in Northern Ireland. So, thank you very much to David Singleton for his choices. We’ll post the links to all the topics discussed so you can decide for yourself whether they should indeed be better known.