In 2011, Smartphones are ubiquitous and everyone and his dog is writing mobile apps, but using apps when you're not in range of a fixed wifi hotspot or standing still in an urban area is often extremely frustrating. How often have you tried to refresh and found yourself staring at an interminable spinner that makes you want to throw your phone at the wall? Here's why (and a plea to app developers to do something about it!)

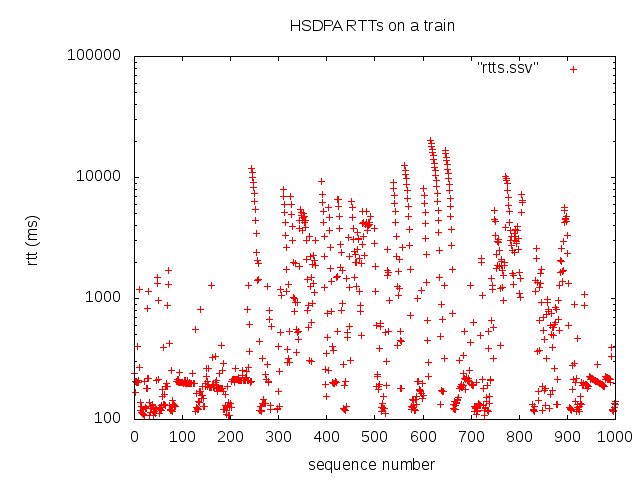

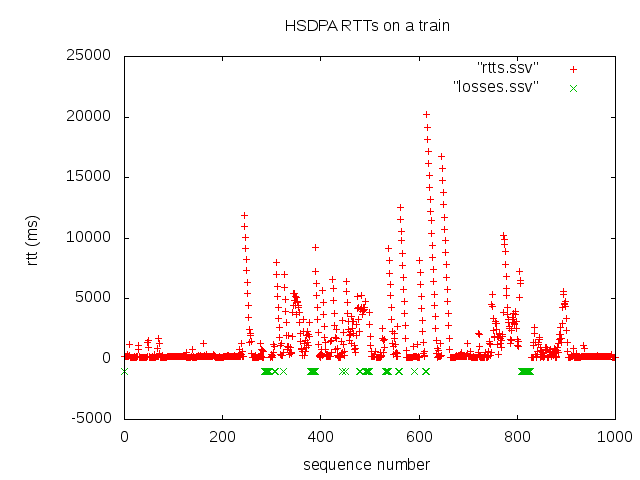

The graph above shows the round-trip time (RTT) for 1000 IP packets I traced over a supposed super-fast HSDPA connection while travelling on a train in the UK. All the while, my phone had signal, though it was switching pretty frequently from HSDPA to (still supposedly broadband-speed) 3G. But apps on the phone were totally useless for anything involving a network connection - refreshing resulted in nothing more than a spinner.

What can we see here?

On wired connections, such a long RTT as 20s just wouldn't be seen, so what's going on? The underlying radio connection is flaky, but 3G data connections make their own attempt at implementing reliable delivery. So when the radio link comes back, buffered packets will still make it to/from the device. Hooray, we've compensated for the flaky radio connection and all those great apps should work great, right? Wrong.

Most apps communicate with the services they depend on in the cloud via HTTP which in turn uses a TCP connection to transfer data reliably and have the parts of every request and response show up in the right order. TCP gives us reliability by re-transmitting packets which haven't been acknowledged (i.e. a corresponding packet returned from the other end of the link) within its estimate of the round-trip time of the connection. TCP assumes that the connection has a more or less constant RTT and assumes delays are losses due to congestion somewhere on the path from A to B. To avoid overloading the network and give the congestion a chance to clear, TCP backs off - waiting longer and longer on each loss to send the next packet.

On our mobile link, with an underlying reliable data connection but with highly variable delay, there is little/no loss and no congestion, but of course TCP doesn't know that and backs off making the connection our apps see next-to-useless. The same effect means that running TCP over TCP (with or without a mobile link underneath) is also a bad idea, as described in this excellent article by Olaf Titz: Why TCP over TCP is a bad idea.

So what can you do as a mobile developer? I'm not suggesting that everyone should go out and implement their own proprietary reliable-but-delay-tolerant protocol over UDP - you're unlikely to do a better job than TCP (though maybe somebody should :-) ), but there are a couple of practical things you could try. In the above trace, you can probably see that established TCP connections which haven't managed to transfer data yet (due to lots of exponential backing off) are unlikely to recover and when the underlying connection "comes back" will not perform as well as a newly established TCP connection. If your application needs to transfer relatively small amounts of data in response to a user action you could try setting aggressive timeouts and retrying with new TCP connections. You may also choose to avoid the system's HTTP stack and open TCP sockets directly, since the system stack will often re-use an already established HTTP connection to the same host - a great idea in a system with constant delay since the TCP connection will already be "up to speed", but not so great in the conditions above. If you do this, you'll probably want to keep track of the type of connection in use and only apply these tweaks when on a mobile link. Most mobile app platforms provide a mechanism to discover the underlying link type (for example Android's ConnectivityManager). More importantly, this is (another) reason to build a great offline / flaky mode for your app so that users aren't quite so frustrated by those spinners.

Here's a closer look at the variance in RTT - the y-axis is a log scale.